By John Johnson

By John Johnson

A three-year epidemic of “Asian flu” has had a devastating effect on the United States. While this disease has not directly affected the health of U.S. citizens, it has drastically impacted the profitability and future of the U.S. textile industry through a continuing flood of cheap, imported textiles and apparel.

The Textile Division of Plains Cotton Cooperative Association (PCCA), especially Mission Valley Fabrics (MVF) in New Braunfels, Texas, has not been immune to the relentless spread of the disease. In an effort to stop the hemorrhage of financial losses at Mission Valley, PCCA announced in early May that major changes would be made at the New Braunfels mill.

MVF is converting all of its manufacturing capacity to denim and halting production of yarn-dyed, woven fabrics. The move will enable the mill to retain approximately 40 percent of its workforce in New Braunfels, more than 200 jobs, for spinning, weaving and finishing operations related to denim manufacturing.

The effort will result in the loss of 370 management, sales and production jobs throughout Mission Valley in addition to 49 manufacturing jobs already curtailed. More important, PCCA will re-focus its value-added processing on a product with which the cooperative has experienced tremendous success in the past because denim remains the most popular apparel item among American consumers. Meanwhile, denim is not a new product line for MVF.

“Soon after our acquisition of Mission Valley in 1998, we began manufacturing some denim there, comprising as much as 33 percent of its product mix at one point,” PCCA President and CEO Van May says. “During that time, we also completed a major renovation of Mission Valley’s yarn manufacturing and weaving equipment which will enhance our ability to make denim in New Braunfels,” he continues.

“By completely converting Mission Valley to a denim facility and adding the production to that of American Cotton Growers, PCCA will increase its annual capacity 30 percent to approximately 52 million linear yards or about 10 percent of total U.S. denim manufacturing capacity,” May adds.

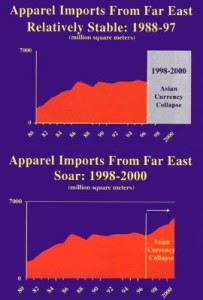

The Asian flu began in late 1997 when an economic crisis spread throughout the region sending currency values tumbling in a domino-like effect. The resulting chaos forced Asian consumers to cut spending, and textile and apparel manufacturers there had to seek markets elsewhere in an effort to export their way out of financial trouble. Thus, their sights turned to the most affluent marketplace in the world: the United States.

The Asian collapse was preceded in 1997 by the U.S. textile industry’s second highest profits ever—$1.9 billion on record shipments of $83.9 billion. That was followed by the first three-year domestic industry contraction since the 1950s as U.S. fiber consumption for apparel and home furnishings fell 13 percent.

In calendar year 2000, the huge increase in foreign imports resulted in an after-tax loss of hundreds of millions of dollars for U.S. textile mills, the first such annual loss ever. Also, more than 55,000 textile jobs have been lost nationwide during the past two years as manufacturers closed unprofitable plants or cut production schedules. Both financial and job losses have continued thus far in 2001.

U.S. textile manufacturers, including PCCA, spend millions of dollars annually complying with federal and state regulations and attempting to be good employers and stewards of the environment, Van May said.

Through June, the average value of many Asian currencies relative to the U.S. dollar remained at levels 40 percent below what they were prior to the economic crisis. When coupled with the strongest dollar in many years, the effect is like a double-edged sword. Asian-made apparel is much less expensive, and U.S. consumers have even greater buying power leaving domestic manufacturers with little or no competitive advantage in the marketplace.

“U.S. textile manufacturers, including PCCA, spend millions of dollars annually complying with federal and state regulations and attempting to be good employers and stewards of the environment,” May says. “Then, we are expected to compete head-to-head with foreign manufacturers who pay their workers ridiculous wages and offer them few, if any, benefits. Couple that with a 40 percent currency advantage and it’s just too much,” he continues.

“Consequently, they can sell their yarn-dyed fabrics at prices well below our cost of production, and that situation will only worsen with the approach of 2005 when all quotas will be lifted under provisions of the World Trade Organization (WTO),” May says. But, not all apparel imports are entering the United States legally.

According to the American Textile Manufacturers Institute (ATMI), some foreign manufacturers are illegally transshipping apparel products to the United States by lying about their country of origin to avoid U.S. quotas. Meanwhile, some foreign countries have illegally raised their import tariffs and other non- tariff barriers to effectively block U.S.-made goods.

These activities have prompted ATMI to ask Congress for additional funding for the U.S. Customs Service which is responsible for stopping illegal textiles and apparel at the border. The organization also wants Washington to enforce trade regulations in countries that have closed their markets to U.S. products.

“No one could have predicted a situation like this when PCCA was acquiring Mission Valley in early 1998 and diversifying the cooperative’s textile product mix,” May explains. “The year before, Mission Valley’s sales exceeded $70 million, but we realized that was an exceptional year. So, we based our decision to purchase the mill on more realistic expectations of annual sales in the neighborhood of $50 million.”

In its first month of PCCA ownership, Mission Valley posted net margins of more than $500,000. Since then, however, competition from imports sent the mill’s earnings into an unending, downward spiral. For a time, it appeared new trade legislation would provide some relief.

“PCCA and the rest of the U.S. textile industry fought hard to win Congressional approval of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) and improve our competitive position relative to the Asian imports,” May says. “We then spent nine months studying ways to best utilize the CBI, but we ultimately determined it would not provide enough advantages to save the domestic yarn-dyed market.” That knowledge became the foundation for PCCA’s decision and the message delivered to Mission Valley employees whose jobs would be eliminated.

“We deeply regret the loss of jobs that will result from our conversion away from our traditional yarn-dyed, woven fabrics,” MVF Plant Manager Bryan Gregory told employees and local media on May 3. “However, we have concluded there is no profitable future for these products and, like almost all U.S. textile manufacturers, Mission Valley must adapt to the increasingly competitive and rapidly changing marketplace in order to survive,” he said.

A number of key factors are in PCCA’s favor as it re-focuses solely on denim production. Denim manufacturing has provided net margins for the cooperative throughout the Asian crisis despite a soft domestic denim market. During this time, U.S. denim production capacity has become better balanced with demand as other mills reduced or curtailed denim operations. And, PCCA has increased significantly its denim customer base during the past two years.

“The conversion of Mission Valley to a spinning and denim weaving and finishing operation will require some financial investment,” May says, “but it is the least expensive of all the alternatives we considered. Denim margins remain very narrow, but there are encouraging signs. Demand for denim in Europe is booming, and the U.S. market traditionally has followed Europe’s lead when it comes to apparel.”

Some might call PCCA’s decision regarding Mission Valley a “back to basics” approach to a most difficult market situation. But, those who know PCCA best will recognize it as another example of the kind of vision that enabled the cooperative to become one of the most successful agricultural endeavors in U.S. history.