By John Johnson

Charles Abernathy – 1945

It had been more than 56 years since they last saw each other; two men who shared more than an average bond that develops between soldiers in combat. One had saved the other’s life.

Now, sitting in a Sevierville, Tenn., restaurant with his wife, daughter and son-in-law, PCCA Director Charles Abernathy of Altus, Okla., was apprehensive. Would he be able to recognize former Lieutenant Sharp after more than a half century? Following the end of World War II, he often thought about the young lieutenant he highly respected.

In recent years, Abernathy had attempted to locate Sharp, but he could not remember the officer’s first name. In wartime, soldiers often prefer to know each other by last name only as a means to avoid building friendships that can be snatched away so quickly and mercilessly in battle.

Likewise, Leo Sharp could not forget the young infantryman from Oklahoma who saved his life that fateful morning on Okinawa in late April 1945. He and Abernathy first met on the island of New Hebrides in 1944 as members of the Army’s 27th Division.

“We just hit if off,” Abernathy says. “He was a good man.” The two soldiers served in different platoons; Abernathy was assigned to 2nd Platoon, and Sharp commanded 4th Platoon.

“I was 20 years old when I enlisted in the Army in 1943,” Abernathy explains. “I was living on a farm in Jackson County, Oklahoma, I had received a farm deferement from the Selective Service, and I had been married 10 days when I enlisted,” he adds. “I thought I ought to go (volunteer for military service), so I did.”

Abernathy and 150 other soldiers arrived at New Hebrides in early 1944 after sailing 30 days on “an old liberty ship.” The island is approximately 600 miles due west of Fiji in the South Pacific. By late October of that year, plans for the invasion of Okinawa were underway because the island was viewed as the base from which allied assault troops could stage and train for an eventual attack on the Japanese mainland.

Code-named Operation Iceberg, the invasion involved a huge naval armada and 182,000 U.S. assault troops. It began April 1 (Easter Sunday), 1945. The invasion force consisted of three Marine divisions and four infantry divisions of the 24th Army Corps including Abernathy’s and Sharp’s 27th Division.

The landings were made virtually unmolested along five miles of beaches on the west coast of southern Okinawa. The Bishigawa River divided the Marine’s sector to the north and the Army’s to the south, but the troops were completely unaware the Japanese had left the beaches intentionally undefended. They soon would learn approximately 100,000 Japanese troops were well entrenched in caves, behind cement tombs and other fortifications on higher ground further inland.

Each squad was assigned a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) for greater firepower than was possible with the rifles carried by most infantrymen. The .30-caliber BAR could fire up to 550 rounds per minute, and it was Abernathy’s weapon on Okinawa. Ironically, he had “won” what he considered the privilege of carrying the BAR in an earlier competition among members of his battalion.

“I was picked along with several other men to see who could break down, accurately name the parts and reassemble the BAR the fastest,” Abernathy explains. The prize, in addition to carrying the BAR in combat, was a case of beer.

“I was the least interested participant in the competition because I didn’t drink,” Abernathy continued. “The other men wanted that case of beer real bad, and it must have distracted them because they couldn’t put their rifles back together correctly. I just took my time reassembling the BAR, and I won.” Abernathy made some soldiers both happy and unhappy that day.

“I didn’t want the beer so I gave it away,” he says. “The men who got a bottle of beer were real happy, but the ones that didn’t were pretty upset.” Abernathy’s BAR later would play a pivotal role in battle.

About three weeks after the initial assault on Okinawa, Abernathy and other members of the 27thDivision found themselves along a rocky ridge in the dark of night. Soldiers who carried the BAR were assigned an assistant. That night, Abernathy and his assistant dug the best foxhole they could in the rocky earth and took turns sleeping while the other kept watch.

“It was about 4 a.m. when my assistant woke me up and said ‘they’re here,'” Abernathy explains. “I immediately saw the enemy and opened fire with my BAR while my assistant kept handing me magazines full of ammo.” The moment he heard the first shots, Lt. Leo Sharp ran to Abernathy’s position.

“Lt. Sharp started reloading the spent magazines so I could keep firing” Abernathy says. “I was the only one firing because I was the only one who could see the enemy.” The withering fire from his BAR forced the attackers to halt their advance and take cover. “I fired so many rounds I thought the barrel on that BAR was going to melt,” Abernathy continues.

Later, as dawn began to break, Lt. Sharp saw movement and said, “Abernathy, if you will go with me, I’ll slip a grenade in the hole there.” As they moved forward, the two GIs saw three Japanese soldiers preparing a 25-pound satchel charge to throw at the Americans. Perhaps in a rush of adrenaline, Sharp pulled the pin from his grenade but mistimed his throw. There was time for one of the Japanese soldiers to grab the grenade before it exploded and toss it back at the two Americans. At that moment, Abernathy opened fire with his BAR, and the grenade fell harmlessly away. It was that event for which Sharp credited Abernathy with saving his life.

Later, the American soldiers moved forward until Japanese machine-gun fire began. A sergeant was hit, and Abernathy pulled the wounded man into a nearby hole and applied a tourniquet as he called for a medic. The medic and Abernathy then carried the wounded sergeant to an aid station.

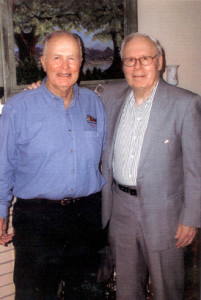

L-R: Charles Abernathy and Leo Sharp – 2002

After he returned to the fight, a sniper’s bullet hit one of Abernathy’s phosphorous grenades, igniting it and causing a severe burn on his leg. He went back to the aid station where the wound was quickly wrapped then returned to the front line where his BAR was needed.

“For the next three days, I went back to the aid station each morning to have the wound dressing changed,” Abernathy explains. “Finally, a doctor told me if I didn’t get better care I would lose my leg. That got my attention, and I boarded a hospital ship that would take me to Guam.”

The first night out of Okinawa, the ship was attacked and hit by kamikazes. Again, Abernathy found himself assisting the wounded by holding plasma and a flashlight for doctors and nurses.

Abernathy eventually returned to his unit on Okinawa where fighting continued until late June. For his heroism the previous April, Abernathy was awarded the Silver Star.

The commendation reads, in part, “His coolness, initiative and courage saved the lives of not only the officer (Lt. Sharp), but the men of his company as well.” Abernathy also received the Purple Heart for the wound he received in battle, and when the war ended, he and Sharp were among the first allied occupation troops on the Japanese mainland.

“I stayed in Japan until December 1945 when the 27th Division was broken up, and I shipped out for the United States,” Abernathy recalls. “I arrived in Seattle on Christmas Eve night 1945.” He would not see Lt. Sharp again for almost 60 years.

Sharp, meanwhile, remained in Japan until July of the following year. Eventually, both men would return to their respective homes in Southwest Oklahoma and Eastern Tennessee. Both would be farmers and successful businessmen, and both would share the same, haunting question for decades: What ever happened to…?

Fortunately, Sharp remembered Abernathy’s first name, Charles, and that he was from Altus, Okla. In late 2001, Sharp’s son found Abernathy’s address on the Internet, but the former lieutenant was cautious.

“Everybody doesn’t want to be found,” Sharp told his local newspaper. So, he sent a Christmas card to Abernathy, and plans for a reunion soon were underway. They agreed to meet first at a restaurant in Sevierville, Tenn., where Sharp lives.

Charles Abernathy sat in the restaurant last January, and thoughts, questions and memories flooded his mind as he anxiously waited. Finally, he saw a cap with the words 27th Division emblazoned on it, and the two veterans spent the next two days reminiscing.

“You can’t imagine what a reunion it was,” Abernathy admits. “He was a special man, and I thought a lot of him as a lieutenant and as a person. He’s still the same.”

“I got so excited at seeing him and sharing experiences with him,” Sharp told a reporter for The Mountain Press. “It was intoxicating.”

Charles Abernathy’s questions finally were answered, and he had another opportunity to thank the “best officer” he served with for his leadership and courage during World War II. Likewise, Leo Sharp was able once again to thank the man who saved his life that fateful morning so long ago.