By John Johnson and Chris Kramedjian

As far as U.S. row crops go, cotton is particularly susceptible to foreign exchange. As opposed to U.S. grains, the vast majority of U.S. cotton is exported to our country’s trading partners. The U.S. Department of Agriculture currently predicts 80 percent of 2018 production will leave the country by the end of the marketing year on July 31, 2019. That much is common knowledge, but fewer people are familiar with the challenges that importing countries face, especially with regard to managing foreign currency.

U.S. companies are uniquely privileged in international trade since the U.S. Dollar is the main currency of international trade. Most international deals are transacted in U.S. Dollars. For many other countries, this arrangement adds another step of complication. Before foreign buyers can pay for U.S. cotton, they first have to buy U.S. dollars. When that country’s currency weakens against the U.S. Dollar, the buyers will have to spend more of their home country’s currency just to buy the same number of dollars they need to purchase the cotton. When the importers’ currency strengthens against the U.S. Dollar, less of their money is needed to purchase the same number of dollars needed to buy cotton. So, for many of the countries that import U.S. cotton, large movements in the value of their currency can be more important than changes in the price of cotton.

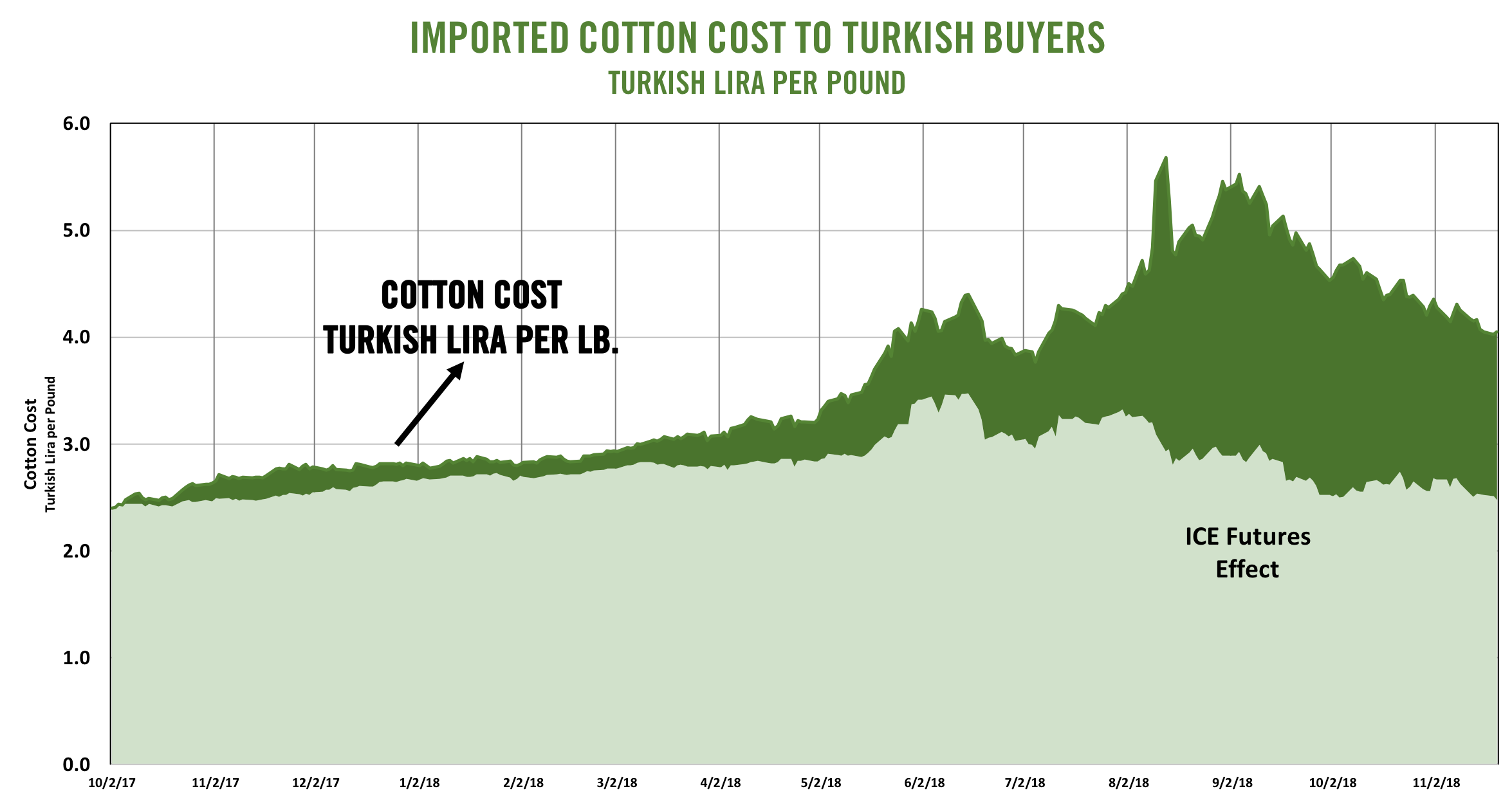

A perfect example is Turkey, a reliable customer for many years. A deepening economic crisis in Turkey caused its currency, the Lira (TRY), to plummet. From April 2 to August 13, the Lira fell almost 73 percent in value versus the U.S. dollar. Since textile mills in Turkey must buy dollars in order to purchase U.S. cotton, mills that would have normally imported U.S. cotton were forced to focus on domestically-grown cotton, which does not require exchanging currency. However, Turkey’s farmers only produce about 63 percent of cotton needed by the country’s textile industry, thus mills eventually will have to import cotton to meet their needs. Fortunately, the Turkish Lira has partially recovered since August as economic and political tensions eased, putting U.S. cotton back in reach of Turkish buyers.

The Lira’s loss of value has been attributed to Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdogan’s opposition to the country’s Central Bank raising interest rates to control inflation. Erdogan wanted to keep interest rates low to encourage borrowing and investment in infrastructure. However, the bank eventually raised interest rates. The move enabled the Lira to stabilize and rebound somewhat against the dollar but not back to previous levels. The United States’ increased tariffs on Turkish aluminum and steel contributed to the turmoil and uncertainty, and Erdogan imposed retaliatory tariffs on imports of U.S. products such as cotton.

The dramatic devaluation of the Turkish Lira peaked in early August. Since then, it has recovered but not to levels before the economic crisis began.

Turkey’s Lira was not the only currency to suffer a big devaluation this summer Several other countries also saw dramatic depreciations. There were several political factors influencing international exchange rates, but two specific factors outweighed the others. First, the U.S. Federal Reserve continued to increase interest rates this year, which made U.S. deposits and, therefore, U.S. Dollars more attractive to international investors. Secondly, in October, the price of oil rose to its highest level in almost four years, which had a particularly severe effect on import dependent economies. Countries like Indonesia, for example had to buy more and more U.S. Dollars just to buy the same amount of oil, decreasing the value of the Indonesian Rupiah in the process.

At the same time that foreign currency weakness made U.S. cotton more expensive for importers, it also made the export market more attractive for foreign cotton exporters. In India, where exporters buy local cotton in Indian rupees but sell internationally in U.S. dollars, rupee depreciation opened pricing opportunities.

“U.S. competitors have enjoyed a big advantage price-wise, giving them more bargaining power,” said PCCA Vice President of Marketing Keith Lucas. “We’ve had to be more selective in the way we offer cotton and more deliberate about when we offer it,” Lucas said. “Fortunately, we’ve been able to maintain a reasonable pace of sales.”

While the trade dispute with China has garnered the headlines, the strength of the U.S. Dollar and its impact on foreign currencies have been a very significant factor to both price and sales

“We need a resolution to these trade disputes so we can get back to the cotton demand levels we’ve seen in recent years,” Lucas said. “They are affecting all segments of U.S. agriculture, not just cotton.”