By Pamilyn Scott

Photo courtesy of Texas Agricultural Experiment Station

The absence of an area-wide boll weevil control program will require constant vigilance among individual Texas High Plains cotton producers in 1997 to keep in check the devastating pest that causes millions of dollars in losses annually. This personal responsibility may be compounded by the largest weevil numbers seen throughout the area based on early data.

This year’s situation resulted when the Texas boll weevil eradication program was derailed by a state supreme court ruling which found the Texas Legislature delegated too much authority to the Texas Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (TBWEF) which managed and collected assessments to fund the program. The ruling, in effect, killed the program. However, State Senator Robert Duncan of Lubbock sponsored a bill to revise and revive the boll weevil program. The bill quickly passed through the legislature and was signed by Governor George Bush.

The new program will be supervised by the Texas Agricultural Commissioner, and programs previously halted in South Texas, the Southern Rolling Plains and the Central Rolling Plains are back in operation as before.

Meanwhile, a referendum has been scheduled for the Southern High Plains Caprock Eradication Zone to determine if producers there wish to reactivate the program. Ballots must be postmarked by August 1, and each section of the referendum must pass by a two-thirds majority. If approved, an eradication program could be initiated there this year, depending on time constraints.

In the Northern High Plains Zone, pest management strategy is another story because a referendum for that area’s producers has not been scheduled. Thus, individual producers must decide if and when spraying for boll weevils is necessary this season.

Pheromone trap data collected to date shows large numbers of boll weevils survived the winter in many High Plains counties. Infestations are heaviest in southern counties and decrease in intensity to the north; however, infestations are expected to increase in both zones.

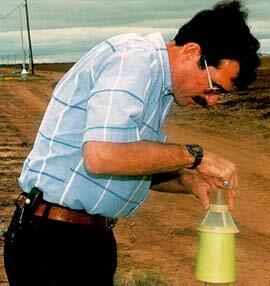

Dr. Jim Leser checks a pheromone-baited boll weevil trap. Photo by Pamilyn Scott

“Fewer acres being treated, greater overwintering sites in the form of CRP fields, and milder winters led to increased weevil numbers,” says Dr. Jim Leser, entomologist/pest management at the Texas Agricultural Extension Service (TAEX). “We are estimating numbers to be 20 times greater than last year.”

Five million acres were treated in 1995, but questions arose persuading half the cotton producers across the area to withhold payment of their assessments that helped fund the Enhanced Diapause Program managed by Plains Cotton Growers (PCG) with authority from TBWEF. Consequently, the program suffered due to lack of funds as only 3.0 million acres of the 6.5 million needing treatment in 1996 were sprayed. The spray program simply was not able to treat all of the necessary acres, and the intervals between treatment was too wide to be effective, explains Leser.

“Too many farmers assume cold winters alone take care of the boll weevil problem,” says Leser. “They need to understand it is a combination of cold winters and the PCG spray program that actually controlled weevil problems in the past.”

With these types of projections and no coordinated spray program, producers must implement their own preventative strategies. PCG and the TAEX hope to assist farmers by providing data collected by PCG traplines and Agri-Partners traplines. The organizations also encourage growers to utilize personal traps and crop consultants to establish a spray program.

Producers are encouraged to utilize and check their own traps to know which areas need to be treated. A crop consultant can provide farmers with information concerning what chemical needs to be sprayed, how much needs to be applied and at what rate. Data from PCG and Agri-Partners traplines will be published on DTN, the Internet, in newspapers, and the TAEX website to inform growers of infested areas. PCG encourages growers to submit their personal trap findings to be published to help locate areas of weevil infestation.

“When farmers spray early, to them it appears they are losing money,” says Leser. “Farmers won’t lose as much yield if they spray overwintered weevils early, and the cost will balance out later.”

Leser recommends spraying if an average of four or more weevils are captured per trap during the week that pinhead squares first appear. Two to three applications prior to blooming delays a large infestation of weevils later. Spraying must stop before the first bloom, however, or the insecticide eliminates “beneficial insects” that control other pests.

“Producers spraying before mid-August are treating ‘their’ weevils, but when weevils begin to move, a farmer is treating weevils from his neighbor’s acreage if he doesn’t have a spray program,” explains Leser. “The previous area-wide spray program worked because everyone was treated.”

To further weevil control, Chad Raines, boll weevil operations assistant at PCG, suggests stopping unnecessary new boll growth after cotton matures. Growth regulators halt growth, thus preventing weevil feeding later in the season. Raines also recommends adding a chemical such as methyl parathion that kills weevils in the diapausing stage when applying harvest aids. It is a more costly procedure, but it is beneficial for the following year’s crop, says Raines.

It is estimated most farmers would spend more money by implementing an individual spray program as compared to much lower control costs under an area- wide spray program. According to the Boll Weevil Economic Impact Study conducted jointly by Texas A&M and Texas Tech Universities, it is estimated that insect control costs in the southern High Plains could have an average increase of $35 to $45 per acre on irrigated land and $20 per acre on dryland due to the boll weevil. Costs in the High Plains diapause control program have averaged about $12.50 per acre per year.

Throughout its history, the area-wide boll weevil control program that began in 1964 proved successful, but as its future on the High Plains is temporarily in limbo, farmers once again can depend on PCG and TAEX to provide information about weevil emergence and infestation. Incorporating personal control efforts and encouraging neighboring producers to do likewise can help decrease problems later in the growing season.