By John Johnson

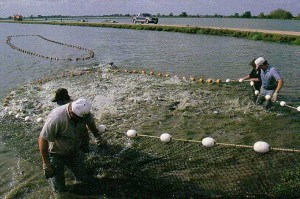

Eldon Penner and crew seine catfish for delivery to market. Photo by John Johnson

Aquaculture has developed into the fastest growing segment of U.S. agriculture in recent years. Defined as the farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, crustacea, etc., aquaculture was practiced in China as long ago as 2000 B.C. More recently, farmers in Wharton County, along the Upper Coastal Bend of Texas, have been making a splash of their own in this growing market.

The U.S. aquaculture industry increased four-fold during the 1980s to a farm value of $762 million in 1990 and was valued at more than $1 billion by 1995. Per capita consumption of seafood in the United States currently is estimated at about 15 pounds per person annually.

According to some estimates, seafood imports are the largest contributor to the U.S. trade deficit among agricultural products and second largest, after petroleum, among all imported natural resources. In 1995, approximately $6.7 billion worth of seaford was imported into the United States. During this same time, the country exported $3.1 billion worth of seafood.

Figures released by Texas A&M University (TAMU) show an estimated 672 operators involved in aquaculture as of October 2000 producing more that 11.8 million pounds worth $38.35 million. Perhaps it is why Wharton County producers and others are diversifying into aquaculture.

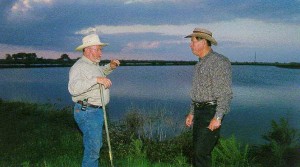

In late October, Dettling surveyed his pond’s harvest potential for the 2001 crop. Photo by John Johnson

Catfish production is by far the largest segment of U.S. aquaculture, valued at approximately $417 million in 1996. TAMU reports the same is true in Texas with 320 catfish operators producing 2.5 million pounds valued at $3.25 million.

Wharton County’s Eldon Penner is one of the state’s catfish producers. A diversified farmer, Penner’s 85 acres of catfish ponds are located a few miles southwest of Danevang Farmers Coop Society where he purchases fuel and other supplies.

Despite an average start-up cost of $5,000 per acre for catfish production, Penner seems undaunted. He seines every week, shipping an average of 15,000 pounds of catfish per week to a processing facility near Houston.

“Feed is the most expensive item in my operation,” Penner explains. “We feed 150 pounds per pond-acre per day,” he adds. Forward contracting for harvested catfish is not an option. “Processors pay us and other catfish farmers whatever the going price is the day fish are delivered.”

Hybrid Striped Bass may be the least-known form of aquaculture. In fact, there are only two producers in Texas, according to TAMU. One of them is Jim Ekstrom of Silver Streak Bass Co., a division of Ekstrom Enterprises, in Wharton County. Annual Hybrid Striped Bass production in the United States currently is nine million pounds with Texas accounting for 2.5 million. At 1.5 million pounds per year, Ekstrom’s operation is the third largest in the country.

Bass production is “very capital intensive,” according to Ekstrom, also a patron of Danevang Farmers Coop. Start-up costs are estimated at $10,000 per acre, and the fingerlings cost three times as much as catfish. Consequently, Ekstrom spent two years developing a concept and business plan before obtaining financing to buy land and start his own aquaculture operation. It took another two years to build 500 acres of ponds. At peak harvest, Ekstrom delivers 40,000 pounds per week to Houston processors.

Pincher’s restaurant in El Campo, TX. Photo by John Johnson

Bass feed contains cottonseed meal, and it takes 18 months for fingerlings to reach a desired harvest weight of 1.5 to 2.0 pounds. Ekstrom also notes Hybrid Striped Bass have fewer disease problems compared to catfish, but they are more sensitive to water quality

“We have two wells, one with a capacity of 3,500 gallons per minute, pumping ground water into our ponds to keep them at a constant level,” Ekstrom explains. “We never use surface water due to competition for the resource from petro-chemical plants a few miles away and to prevent introduction of trash fish and pathogens into our ponds.”

Ekstrom is quick to note that aquaculture has no government price supports or crop insurance like some other commodities. However, government licenses are mandated.

“We must have an aquaculture license from the Texas Department of Agriculture, a discharge permit from the Texas Natural Resources Conservation Commission and, in some cases, an exotic species permit from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department,” he explains.

Chris Dettling (left) explains his crawfish operation to PCCA Director Curtis Jensen. Photo by John Johnson

The surge in popularity of cajun and creole cooking that began in the early 1980s created opportunities for aquaculture operators. A few years later, Chris Dettling, another Wharton County resident, became a crawfish entrepreneur.

“I have 30 acres in ponds north of El Campo,” says Dettling, “and our season runs from January to July.” In the early fall of 2000, Dettling anxiously anticipated harvest as he surveyed his ponds’ production potential.

“There’s lots of crawfish in those ponds, and the price of purged crawfish has nearly doubled in the past year due to production shortfalls in Louisiana,” he explained. “There’s a reason crawfish are nicknamed ‘mud bugs’ because they must be purged with pure water after the traps are hauled in from the ponds, otherwise they would taste just like mud.”

Dettling is one of 18 Texas crawfish producers who delivered an estimated 2.8 million pounds to market in 2000, reports TAMU. Another Wharton County crawfish producer is Craig Radley who converted his rice fields to aquaculture in 1994. Although he delivers his crawfish to customers from El Campo to Victoria, TX, Radley took his marketing plan one step further: he and his wife, Debbie, opened a seafood restaurant in downtown El Campo in March 1999.

“We opened our restaurant, Pinchers, as a way to market our crawfish,” Radley notes. “The last two years, 50 percent of our crawfish production has been sold through Pinchers due to negative market conditions. Normally, this restaurant would only need 10 to 20 percent.”

Obviously, start-up costs for some forms of aquaculture can be staggering, but growing consumption of seafood means growing demand and larger markets for producers like these in Wharton County. Approximately 90 percent of all seafood consumed by Americans currently is imported or from recreational fishing. Penner, Ekstrom, Dettling and Radley must be on to something.