But Bark Contamination May Inhibit Marketability

By John Johnson

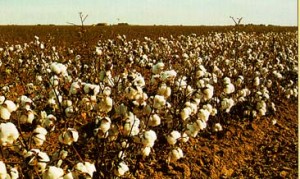

Cotton awaits harvest southeast of Lubbock in early November.

West Texas cotton growers this year may have produced the highest quality crop on record based on early data released by USDA’s cotton classing office in Lubbock. The excellent grade, staple and micronaire readings have a direct and positive impact on marketability, but the “fly in the buttermilk” for some producers in 1996 has been bark content.

“According to the early class data, it appeared the West Texas crop could average an inch and a sixteenth staple length for the first year ever,” says PCCA Vice President of Marketing David Stanford. In fact, the classing office statistics showed through November 28 that more than 77 percent of the 1996 crop was an inch and a sixteenth (staple 34) or longer, with an average staple length of 34.39 for all cotton classed at that time.

Adding to the positive picture was data showing 86.9 percent of the crop was given a color grade of 41 (strict low middling) or better. Finally, average micronaire through the end of October was 38.07 with 72.1 percent of the cotton falling within the premium micronaire range. These quality characteristics normally mean more money to the producer.

“It means our crop truly is tenderable based on this grade, staple and mic,” Stanford explains, “and if it is tenderable, producers have a guaranteed market and a guaranteed basis relationship to the market.” Basis is the cost of certification which includes delivery to a point certified by the New York Cotton Exchange for deliveries and the associated reclassing and warehousing cost. In other words, if the cost is seven cents per pound, producers should sell their tenderable cotton for no less than seven cents off the nearby futures contract.

“Here in the U.S., we have an 11 million bale domestic customer base, and seven million of that is supplied by cotton from the Memphis Territory and Southeastern U.S.,” Stanford notes. “It is enough incentive for West Texas and Oklahoma producers to capture more of this market share.”

Producers and cotton breeders in the two-state area have made great progress in lint quality since the early 1980s as evidenced by this year’s crop. Much of the success is directly attributed to the advent of the HVI (high volume instrument) classing system which has enabled cotton breeders to select and develop new cotton varieties with higher quality characteristics as well as yield potential. But, some producers this year will not realize the full market potential of their crops due to bark content which renders those bales non-tenderable.

“If the cotton is not tenderable, producers have no guaranteed basis or safety net,” Stanford says. “All they have is the CCC loan which is a fixed price for each quality, and currently well below market value.” Stanford explains the international marketplace has its own pricing structure which separates cotton into the “A” (tenderable) and “B” (non-tenderable) Indexes.

USDA’s cotton classing office in Lubbock reported through November 28 that 16.1 percent of cotton classed contained bark. Fortunately, though, the data indicated a downward trend in bark content during the final week of the month. Cotton researchers indicate there may be several reasons for the bark found in some of this year’s crop.

“It appears cotton producers in this area may have been a little too aggressive in harvesting their crops out of fear of bad weather,” says Dr. John Gannaway, professor and cotton breeder for the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station at Lubbock.

“The cotton plants are larger than normal this year,” Gannaway explains, “and producers needed to slow down their strippers and make adjustments in the equipment.” The cotton breeder also notes air temperatures this fall may have slowed the defoliating effects of harvest aid chemicals, and early harvest may have begun before the plants were ready.

“In years like this, producers can have a significant impact on lint quality by making adjustments in harvest equipment,” says Alan Brashears, agricultural engineer for USDA’s Agricultural Research Service at Lubbock. “They can minimize the amount of bark by replacing all but one of the bats on a stripper with brushes,” he explains. “They can also widen the stripper rolls to one-half inch instead of the normal one-quarter inch due to this year’s stalk size. I think it is ultimately more profitable to leave a little cotton in the field in order to obtain the highest quality lint possible,” Brashears continues.

Reduced marketability and severe price discounts resulting from bark are a direct result of the difficulty in processing such cotton at textile mills. Cotton contaminated with extraneous matter such as bark lowers yarn manufacturing efficiency resulting in higher production costs and decreased quality.

Efforts are underway to develop ginning equipment and textile manufacturing equipment to reduce or overcome bark contamination. Cotton breeders also are searching for varieties that are less likely to produce bark during harvest. In the meantime, engineers like Brashears continue to urge producers to reduce stripper speed and make adjustments in their equipment.

The difference between tenderable and non-tenderable cotton can be several cents per pound, and that can mean hundreds if not thousands of dollars when applied to an entire crop. Producers, researchers and marketers of West Texas cotton have worked diligently for years to improve the crop’s quality and promote it to merchants and mills around the world. Their efforts are paying off if the 1996 crop quality is any indication.

Until work is completed to develop equipment to reduce or remove bark, or until new varieties that produce less bark during harvest are released, producers must take matters into their own hands and make recommended adjustments on their strippers. The demand for and price difference in tenderable versus non-tenderable cotton can make a huge difference in the producer’s bottom line.